Dear Reader of these Sermons…

Leave a comment2016-03-20 by Jeremy Clarke

Preacher: Christopher Adams

20th March 2016

—

(Editor’s note: Although this is the sermon preached on the occasion of WGMC’s final act of Sunday worship on 20th March 2016, it had in fact already been preached a few weeks previously. However it seemed such a good place to end sermon-wise – or, if you’re landing on this website for the first time, to begin sermon-wise – that it got a second airing on that final Sunday when not only most of the congregation but also many previous members and attendees, not to mention a large number of visitors, were present.)

—

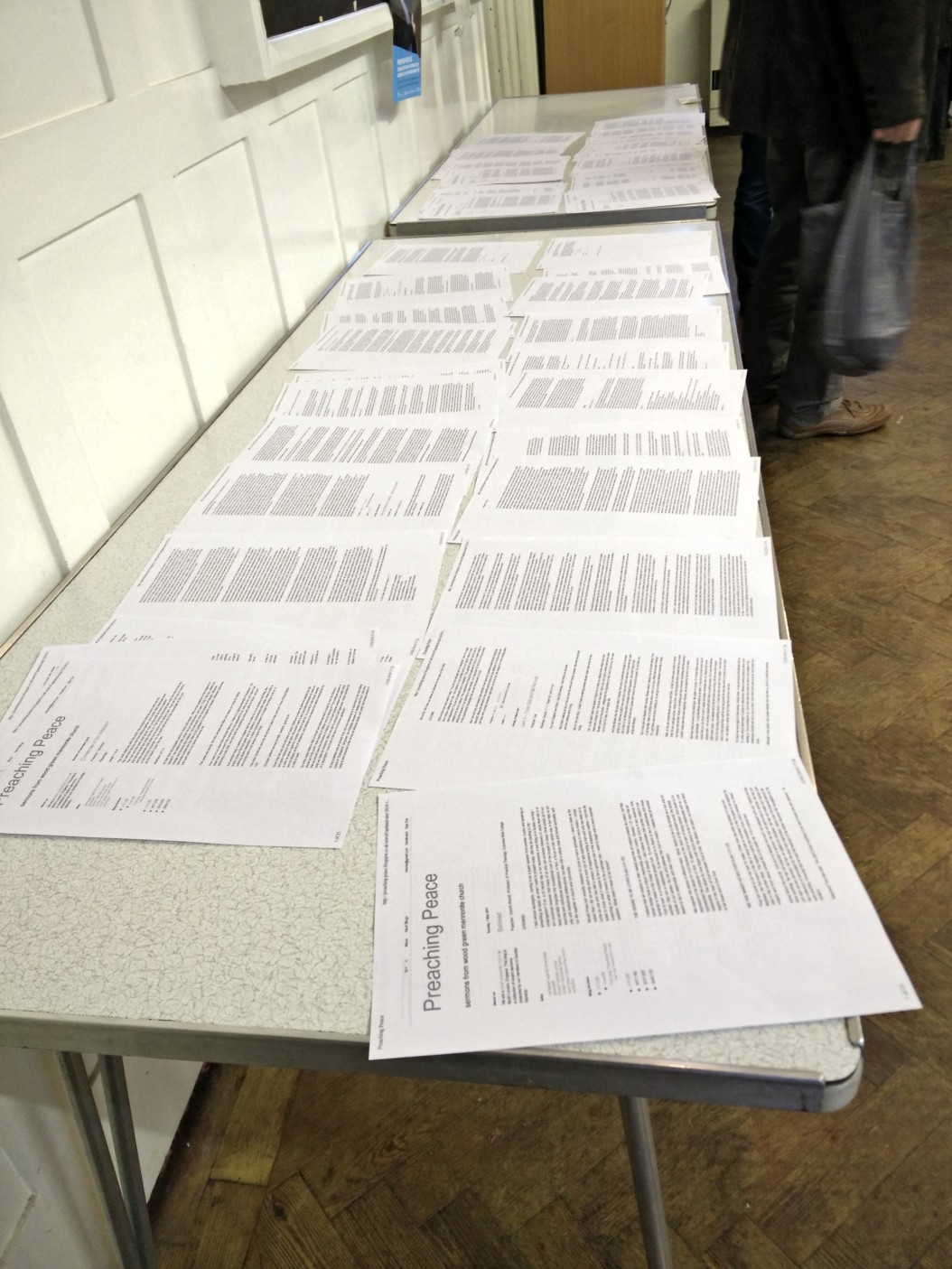

As we conduct our final service, I am very honoured that Sean has asked me to reprise a sermon I preached only a little over a month ago – apologies to those of you who have to sit through this twice! But for those of you who haven’t heard it, some background information. In 2009, members of this church started a preaching blog, collecting all of the sermons and reflections preached at Wood Green Mennonite Church from October 2009 onward, incidentally from the very Sunday I first attend the church. The site has since been maintained regularly apart from a switch from Blogspot to WordPress and collects the sermons preached at the church over the last seven years.

Dear Reader of these Sermons,

What you have before you, waiting to be explored, is an archive – a testament – to the life of a church. Within this corporate life there are individual stories waiting to be discovered, familiar names, dialogues between individuals, but all in the context of a church community whose existence has been instrumental to a Mennonite, and Anabaptist, understanding of Christianity in the UK for the last forty years.

The sermons collected in electronic form on this blog record only the last seven years of this continual conversation, from 2009 until the church’s end in March 2016. The sermons reflect the thoughts, ideals, hopes, struggles, and, particularly, grief of the congregation as it worked through what it meant – and means – to live as a Christian in the modern world.

Living the kingdom of God is a key value reflected in these sermons. While acknowledging the individual’s relationship with and to God, the life of the church sought to explore and to express its Christianity in a way that was deeply corporate. This was perhaps most noticeable in its covenant, and annual covenant services, held in January, serving as both a reminder of the commitment members shared with one another as well as a reaffirmation of moving forward together. A commitment to each other was also expressed through the way the church made decisions – arriving at consensus, often through slow, sometimes torturous meetings, but the church believed that giving everyone a voice, actively listening, and arriving at agreement (even if that was an agreement to disagree) most accurately reflected Jesus’ teaching and was putting into practice the Kingdom of God, here, now, on earth.

Members also met regularly for meals with one another. Homegroups, which met fortnightly, were a place to share, to pray, and to study. A members’ communion, monthly business meetings, walks, protests, lunches – all were ways in which the church came together. The Sunday services, where these sermons were preached, were only a small reflection of the wider – and deeper – life of the church. Indeed, Sunday meetings (held at a civilised hour in the afternoon) were habitually short; service often lasted no longer than an hour. Tea and biscuits afterward, however, could sometimes last longer than the service itself. And as for the sermons themselves: you can see that few are very long at all. Fifteen or twenty minutes was a usual length. Guest speakers with lengthier sermons were indulged if they had something interesting to say, but for the regular speakers, short but insightful was best.

The many names you will come across demonstrate the church’s practice of rotational leadership and de-emphasizing the sermon as the most important portion of a service. The names – Sue, Sue, Wayne, Lesley, Peter, Veronica, Phil, Ruth, Lois, Judith, Chris, Jane, Cheryl, Sean, Mike, Ellie, Alan, Emily, and Simon, to name but a few – are drawn from the congregants, members, and people connected with the church. Their sermons, if read carefully, reflect the characters of their authors. Lesley’s sermons, for example – recorded here before her tragic death in 2011 – show her wit, her humour, her generous spirit and, of course, her immense learning. Indeed, you will find in many of these sermons evidence of wide theological reading. The church – for better or for worse – tended toward the cerebral and its sermons often reflect that fact. Sermon series included a line-by-line analysis of the Lord’s prayer, an examination of Romans, the four Gospels and so forth. Analysis, building context, and drawing on the writing of theologians – from the first century through the twenty-first – were favourite ways of composing a sermon.

This is not to say that these sermons are only pertinent for those with a background in theology. On the contrary, what makes them most potent is their constant insistence on application to real, everyday life – to working out what the text means for us, today, as individuals, and as a church following the teachings of Christ. From Sue’s sermon of 4th October 2009, for instance, we find her asking what the phrase ‘give us this day our daily bread’ means: “is it honest”, she asks, “for [us] to pray ‘Give us today our daily bread’, given that we live in an advantaged, wealthy country? How does the phrase challenge us to become more aware of the us in the prayer, as opposed to praying ‘Give me today my daily bread’?”

For certainly at the heart of these sermons, as indeed at the heart of the church that produced them, is a commitment to “justice, peace, and joy”. Key themes throughout all the sermons are justice, economics, money, distribution of wealth, inequality, the environment, peace, pacifism, gender (you’ll notice the majority of the sermons were preached by women) and bringing the year of Jubilee to the here and now. The Mennonites – of which Wood Green Mennonite Church was one of only two English-speaking congregations in the UK – are an historic peace church and have a long tradition of working with and on behalf of those suffering from oppression, spiritual and physical. The sermons are thus the congregation working out its positions and teachings on the above-mentioned topics. In the sermon series on money, for instance, very real, practical questions were posed: what does it mean to work? What is “enough”? How much is “too much”? How should individual members and the congregation as a whole dispose of their and its income? In the sermon series on the environment, this working out process led to discussions within the business meetings about how the church could support projects as well as encourage its members to lead more environmentally conscious lives. The sermons become conversations between the speaker and the congregation, conversations held over tea, in homegroups, at lunches and distilled in the speaker’s mind in the sermon.

But not all of the sermons were written to teach, or to instruct. While this may appear their primary purpose, they in many instances record the events affecting the church – in the Mennonite and Anabaptist community, in London, and in the wider world – and provide a platform for response. Certainly the most difficult two sermons to read come, painfully, back-to-back. The first was preached by Veronica on 22 May 2011 after Lesley – who preached well and often – died of cancer. Veronica’s text was, in her own words, a “brutal Bible story” – that of Jephthah, who sacrifices his daughter after making a foolish vow. The congregation was grief-stricken by Lesley’s death, and Veronica’s sermon was not so much an analysis of the text as a working through of the church’s very first moments of grief, having already suffered, as Veronica points out ‘a lot of premature death in our congregation in the last eight years’. But while acknowledging the pain we all felt, Veronica turns, suddenly, in her penultimate paragraph to this insight, providing a hard kind of comfort:

One more observation. Last Sunday afternoon when we prayed at the hospice, both Judith and I thought of reading out Psalm 137. I ended up reading it and I missed out the verses we always tend to miss out, the ones about wishing God would kill God’s enemies who are also the psalmist’s enemies. I understand why we leave these verses out, especially in a peace church. But I think maybe I should have read them. Because our enemies are not flesh and blood, but as Ephesians puts it, “the cosmic powers of this present darkness…the spiritual forces of evil.” And as Paul promises the Corinthians, “[Jesus] will reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet [and] the last enemy to be destroyed is death.”

Which makes it even more difficult to read the next post in this archive, dated 5th June 2011. It is Wayne’s liturgy for the farewell to the London Mennonite Centre. The LMC as it was affectionately known was a large, rambling house near Highgate that provided a base for welcoming visitors from across the world. The LMC ensured a strong connection with American and Canadian Mennonites, and provided communal housing for several members of the church at various points in their lives. In 2010 and 2011, however, the LMC was deemed to be no longer sustainable and was sold. The sale set WGMC adrift in many ways and indeed, could be argued, led over the course of the next five years, to the diminishing life in the church and now, its eventual dissolution – and transformation. The sermon series ‘Bible Characters Who Faced Change’ (of which Veronica’s sermon was intended to be the first in the series) grew out of this very real place of loss, grief, and shattered expectations. The church – and the sermons it preached – reflected living Christianity, even if that living was painful, or made us question, or made us afraid, or vulnerable. A great strength of these sermons is their refusal to cover up difficult questions or emotions. Speakers are encouraged to ‘”be real” to say how they feel, to present difficult problems – often ones without easy solutions, or any solutions at all: “Church for grownups”, as was said.

These sermons are our congregation’s testament to a church life well lived. “We are pilgrims on a journey” we sang together frequently. Like pilgrims, we leave traces of our journey behind. Read them. Use them.